Earlier this month, I drove up to Galashiels, in the Scottish Borders, to collect two bales of rather special wool from a sorting depot. My hope is to produce, with the help of long established mills in the North, a cloth that has never before been woven in Britain, despite the rich local textile expertise and abundance of sheep found up and down the country.

You may ask what is so special about this wool and why I think people should know about it.

As a craftsman, I firmly believe in sourcing my material locally, from British producers. Much of the best cloth in the world is still woven in the Northern mills, which I am fortunate to have on my doorstep. However, when it comes to sourcing the raw material for the cloth, localism is an altogether more complex topic, as I discovered when my search for a suiting cloth made from British wool didn’t produce any results.

Unable to find a single producer using local wool in their fabric, I contacted the British Wool Marketing Board, who confirmed that today almost 100% of wool used in British made fabric is imported from overseas. See also the BBC’s article on the ‘English Suit’.

This is despite an estimated 32 million sheep kept in Britain, whose fleeces, as I was about to find out, are too coarse for the use in a modern, light weight and soft cloth. The consequence is that often the wool doesn’t even fetch enough to cover the cost of the shearing. I was appalled and intrigued in equal measures and decided to dig deeper to document what I would find out.

It was a Scottish artisan weaver who told me about a flock of sheep that produce the finest, softest wool, in her home country. The fleece is what has become known as Scottish Merino – a wool that has never been used in a woven cloth in Britain before. Here is why:

The Merino breed, coveted for the finest, softest wool on Earth, originates in Europe, where it was first kept by the kings of Spain. Small flocks of sheep were later gifted to the rulers in Saxony and Britain, before Australia and New Zealand were discovered for their vast pastures and mild climate in the late 1800s, and the tradition ended. Ever since, Merino wool has been imported to the UK from the far side of the globe, to be woven into the fine cloth the British woollen industry is famous for.

Towards the end of the 20th century, increasingly under pressure to find a more sustainable source for the wool, the British government launched – but later abandoned – research into the re-introduction of Merino sheep in the UK. The breed created for this research was a mix of 75% Saxon Merino and 25% Shetland, making it hardy for the Scottish climate.

The sheep, created to give the finest wool under the harshest conditions, were kept at the Macaulay Land Use Research Institute in the Scottish Borders and named ‘Bowmont’, after a water flowing nearby. When project funding dried up after the closure of the institute in April 2011, the flock was dispersed across the UK. One half was taken on by a fine fibre producer in Devon, who is today successfully supplying wool for yarn, however not for weaving but knit wear. The remaining animals stayed in Scotland and were kept on various farms scattered around the country.

I was able to agree purchasing terms with the five individual growers whose wool has been graded at the highest fineness level available in Britain, grade 141 (certified by the British Wool Marketing Board). The wool can easily compete with fleece imported from Australia and New Zealand. Not having initially planned to produce a cloth myself, the project has now evolved from mere story-telling to commissioning the weave of the first ever Scottish Merino cloth. The production chain will be 100% British, from fleece to finished fabric.

Documenting the process and showing all producers involved (including the sheep), in their work environments, will prove that not only do we have the skill and infrastructure but also the raw material to make one of the finest, softest cloths in the world, right here in Britain. If the new cloth can be shown to be successful, the group of growers hope that younger farmers in the region feel encouraged to take on the breed, to help grow the flock and, with that, create a sustainable income source over time.

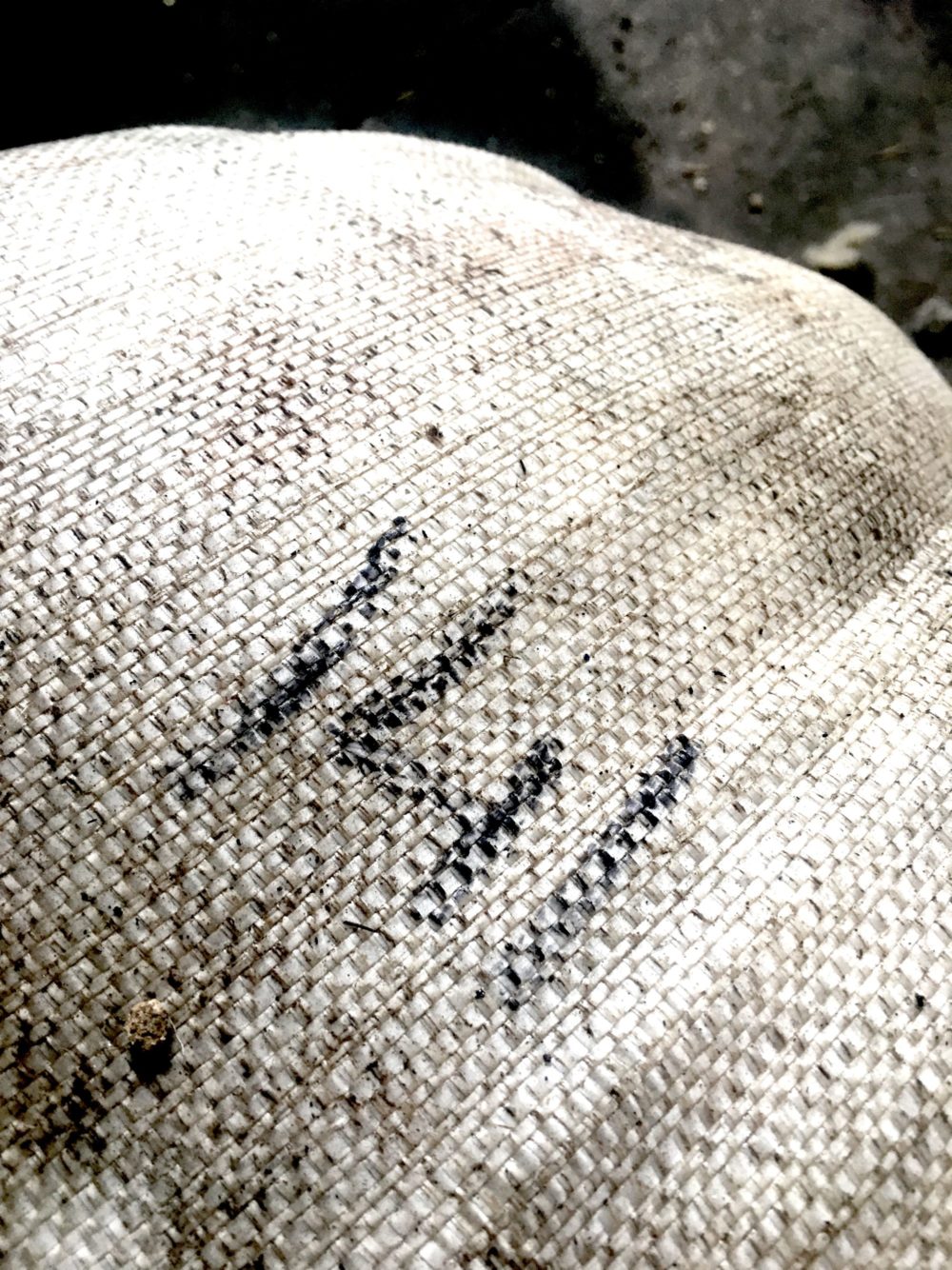

Galashiels Wool Depot